01/

Contact

02/

About

Célio Braga is a multidisciplinary artist

whose/career has been marked by his ability to redefine and to expand

conventional categories such as photography, painting, drawing, textiles and

sculpture, making reference to a broad spectrum of visual language and

traditions of making.

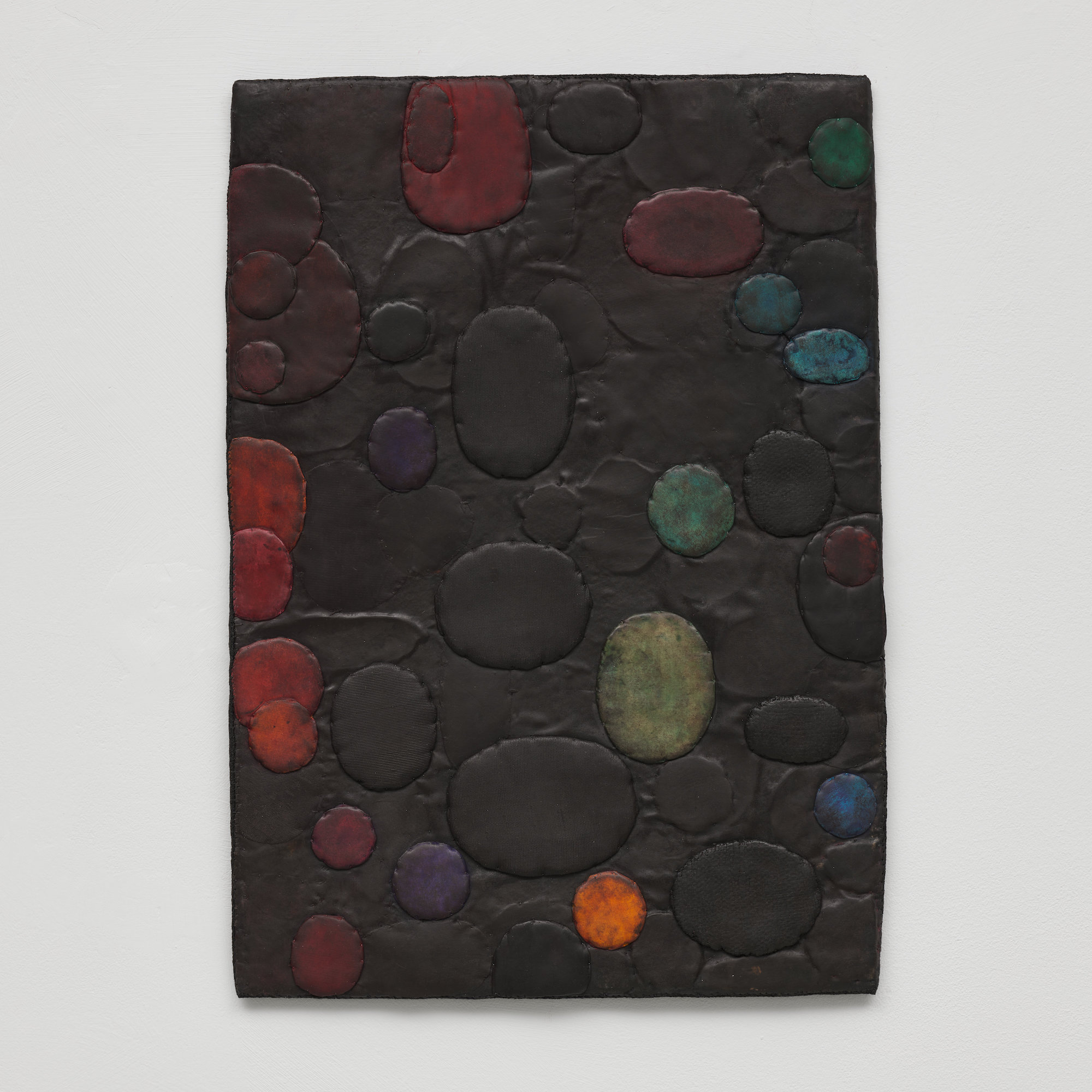

He experiments with different media and pushes them to the limit through successive construction techniques. These time-consuming processes of making include, collage, perforation, layering, mending, stitching, embroidery and weaving, coalescing in a constant process of construction, destruction and reconstruction.

The complex nature of his work embodies a sense of impermanence, doubt and transformation that he considers implicit in the act of creating, both formally and in its potential for generating meaning.

In his recent works, we find elements and formal associations to the openings of the body, the so-called contact zones, to natural growth, to scars, wounds, vulvas, phallus, eyes, tears, blood, mouths, thorns, and teeth. Those elements and visual forms proliferate in rich compositions dealing with themes of sexuality, homoeroticism, religion, gender, violence, birth and death.

The new works are ambiguous in their refusal to be categorized, they are open to a myriad of interpretations which creates a constant friction between bodily presence and absence.

He experiments with different media and pushes them to the limit through successive construction techniques. These time-consuming processes of making include, collage, perforation, layering, mending, stitching, embroidery and weaving, coalescing in a constant process of construction, destruction and reconstruction.

The complex nature of his work embodies a sense of impermanence, doubt and transformation that he considers implicit in the act of creating, both formally and in its potential for generating meaning.

In his recent works, we find elements and formal associations to the openings of the body, the so-called contact zones, to natural growth, to scars, wounds, vulvas, phallus, eyes, tears, blood, mouths, thorns, and teeth. Those elements and visual forms proliferate in rich compositions dealing with themes of sexuality, homoeroticism, religion, gender, violence, birth and death.

The new works are ambiguous in their refusal to be categorized, they are open to a myriad of interpretations which creates a constant friction between bodily presence and absence.

03/

Biography / CV

Célio Braga

Brazil

Lives and works in Amsterdam (The Netherlands) and São Paulo (Brazil)

Education

1996-2000

Gerrit Rietveld Académie, Amsterdam – The Netherlands

Solo Exhibitions

(selection)

2025

-’Perfect Friends - Perfect Lovers’, Phoebus Rotterdam, The Netherlands

-’ENVIESADO’, Massapê Projects, São Paulo - Brasil

2023

-’SKIN . WOUND . QUEER’, KunstMuseum Den Haag, The Netherlands

2022

-‘Flesh and Flowers’, Galerie Phoebus Rotterdam, The Netherlands

2019

-’80 Bullets’ - Barklund & Co., Stockhom - Sweden

-‘Lama e Arco-Íris Azul e Rosa’ - Galeria Pilar - São Paulo - Brasil

2018

-‘The Years . The Tears . The Rainbow . The Endless Sea - PLATINA Stockholm - Sweden

-‘Field of Flowers’, Phoebus Rotterdam - The Netherlands

2017

-‘White Blur’, Phoebus Rotterdam - The Netherlands

2016

-‘Abluções’, Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Goiás - MAC - Goiânia - Brasil (cat.)

-‘Ablutions’, Museu Victor Meirelles, Florianópolis - Brasil (cat.)

2014

-‘MultiColoridos’, Galeria PIILAR, São Paulo - Brasil

-‘GRID’, Hein Elferink Galerie, Staphorst - The Netherlands

2013

-‘Célio Braga (Solo)’, PINTA Art Fair / Galeria Pilar-SP, London - United Kingdom

2012

-‘Pharmacia Deluxe’, Galeria Amparo 60, Recife - Brasil

-‘Litanies’, Galerie Hein Elferink, Staphorst - The Netherlands

-‘Doloridos.Coloridos’, Galeria PILAR, São Paulo - Brasil

2011

-‘Abstrações para Morrer de Amor’, Galeria da FAV - Goiânia - Brasil

2010

-‘Lacerations’, Galerie Hein Elferink, Staphorst - The Netherlands

2009

-‘Unveil’, Teto Projects, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2008

-‘Caio, Felix, Cuts and Perforations’, Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo – Brasil

2007

-‘Recent Works’ Galerie Hein Elferink, Staphorst, The Netherlands

-‘Possible Jewellery and Related Objects’, Rob Koudijs Galerie, Amsterdam -The Netherlands

2006

-‘B.L.U.E’, BalinHouseProjects, London - England

-Galerie Hein Elferink, Staphorst - The Netherlands

2005

-Galerie van der Mieden, Antwerpen - België

-‘Liquescent’, Platina Gallery, Stockholm - Sweden

2004

- ‘Brancos’, Galerie Louise Smit, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2003

- ‘White Shirts’, HuisRechts, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2000

-‘Objeto desejado (e para sempre) ausente’, MAC-Goiás, Goiânia - Brasil

Group Exhibitions

(selection)

2025

-’HAUS OF FIBER’, TextielMuseum Tilburg - The Netherlands

2024

-’A Summer’s Tale’, Josilda da Conceição Gallery, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2023

-’Un-Solid. Still Being Formed’- Célio Braga & Juliette de Graaf’. Josilda da Conceição Gallery, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2022

-’UNTITLED 1, Célio Braga & Yang Ha’. Josilda da Conceição Gallery, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2021

-‘HUID’, BONNEFANTEN Museum, Maastricht -The Netherlands

-‘DE PEST’, Het Valkhof Museum, Nijmegen - The Netherlands

2019

-‘Verdadero es lo hecho’, Museo José Hernández, Buenos Aires - Argentina

-‘HUID’, Tentoonstelling Zaal Zwijgershoek, Antwerpen - België

-‘Black & White’, TextielMuseum Tilburg - The Netherlands

2018

-‘Cultural Threads’, TextielMuseum Tilburg - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘QUEERMUSEU’, EAV Parque Laje, Rio de Janeiro - Brasil (cat.)

-‘Beyond the Body’, Art Center Silkeborg Ban - Denmark (cat.)

2017

-‘EVOÉ’, Galeria Amparo 60 - Recife, Brasil

-‘QUEERMUSEU’, Satander Cultural, Porto Alegre – Brasil (cat.)

-‘HIGHLY VOLATILE’, Vishal Haarlem – The Netherlands

2016

-’TUDO JOIA’, Bergamin & Gomide, São Paulo, Brasil

2015

-‘Born of Concentration’, RAM Foundation Rotterdam - The Netherlands

-‘Under the Skin’, Textile Museum Tilburg - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘Fashion & Mortality’, Lentos Museum Linz - Áustria (cat.)

2014

-‘O que ainda não é’, Galpão TAC, Rio de Janeiro - Brasil

-‘Threads’, Museum voor Moderne Kunst Arnhem - The Netherlands (cat.)

2012

-‘Beyond the Body’, WELTKUNSTZIMMER, Dusseldorf - Germany (cat.)

2011

-‘Us, in Flux’, Lawrimore Project / Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle - USA. (cat.)

-‘ONTKETEND’, Museum voor Modern Kunst, Arnhem - The Netherlands

-‘Drawing Now Staphorst’, Galerie Hein Elferink, Staphorst - The Netherlands

-‘Salon du Dessin Contemporaine’/Galerie Hein Elferink, Paris - France

-‘PULSE Art Fair’/Sienna Gallery, New York - USA.

-‘EMBRACED’, GustavsBergs Konsthall - Sweden (cat.)

2010

-‘THINK TWICE’, MAD-Museum of Arts and Design, New York - USA

2009

-‘SLASH - Paper Under the Knife’ (cat.), Museum of Arts and Design, New York - USA

-‘Start’, Galerie Hein Elferink, Staphorst - The Netherlands

2008

-‘Papier Biënnale 2008’, Museum Rijswijk - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘SOFT (Autonomous Textiles)’, LandsMuseum, Linz - Austrian

2007

-‘Licht’, RC de Ruimte , Ijmuiden - The Netherlands

-‘Hard Candies’, Motive Gallery, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

-‘GlassWear’, Toledo Museum of Art - U.S.A / SchmuckMuseum Pforzheim - Germany (cat.)

-‘Act//’, Huisrechts, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

-‘Fragmentos do Corpo’, Galeria da FAV, Goiânia, - Brasil (cat.)

-‘Focus 4’, KCO CultuurSalon, Zwolle - The Netherlands

-‘2MOVE: Double movement’, Sala Verónicas-Centro Párraga, Murcia – Spain / ZuiderzeeMuseum, Enkhuizen - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘Brazil Art Lounge’, TAC Eindhoven - The Netherlands

-‘.G.E.B.O.R.D.U.U.R.D.’, TextilMuseum, Tilburg - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘Schmuck 2006’, Internationalen Handwerksmesse München - Germany / Museum of Arts and Design, New York - U.S.A

2005

-‘Bock mit Inhalt’, Stedelijk Museum CS, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2004

-‘LOSS’, Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘Doações MAC 1999-2004’, Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Goiás, Goiânia - Brasil

-‘Oogstrelend Schoon’, CODA-Apeldoorns Museum - The Netherlands

-‘Solo’, Galerie Marzee, Nijmegen - The Netherlands

2003

-‘Ravary Project’, Galerie Marzee, Nijmegen - The Netherlands

-‘BLUR, The Bluring of Categories in the Applied Arts’, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam -The Netherlands

2002

-‘FRAU WILLHELM’, Fanshop Amsterdam - The Netherlands

-‘Nature and Time - International Jewelery Competition’, Deutsches Goldschmiedhaus, Hanau – Germany (cat.)

-‘Hair Stories’, Adam Baumgold Gallery, New York - USA

-‘Beziehungen’, Nederlandse Bank, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

-‘DISPLAY’, A Proposal for Municipal Art Acquisitions-2000/2001, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘FILZ FELT’, Landsmunseum für Vorgeschichte Dresden – Germany / Deutsches Textilmuseum Krefeld - Germany (cat.)

2001

-‘SIERADEN’, The Choice of Apeldoorn, Van Reekum Museum, Apeldoorn - The Netherlands / Badisches Landesmuseum Kalsruhe - Germany (cat.)

2000

-‘Eindexamententoonstelling’ - Kunstpaviljoen, Nieuw-Roden - The Netherlands

-‘Annual International Graduation Show’, Galerie Marzee, Nijmegen - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘HAUTNAH’, Kunsthalle, Wien - Áustria

1998

-SBK Ijmond-Noord, Beverwijk - The Netherlands

1993

-‘Bienal do Incomum’, Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Goiânia - Brasil (cat.)

1990

-‘Fragments/Wholeness’, Ariel Gallery, New York - USA

Performances

2010

-’Full Blown/Walking on Flowers’, De Oude Kerk Amsterdam/MuseumNacht 11 - The Netherlands

2009

-‘Similitude’ (with Rose Akras), Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo - Brasil

2008

-‘7 maneiras…’ (with Rose Akras)/VERBO, Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo - Brasil

2002

-‘A self Portrait with many faces’ (with Antonio P. de Souza), De BrakkeGrond, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2001

-‘Natural Diversity’ (with Antonio P. de Souza), The Veem Theatre Amsterdam - The Netherlands

Prizes/Subsidies

2008

-Basisstipendium, Fonds BKVB, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2004

-Startstipendium, Fonds BKVB, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2002

-Startstipendium, Fonds BKVB, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2000

-Marzeer Prize, Nijmegen - The Netherlands

Workshops

2015

- The Skin I Live in (Centro Cultural Valparaiso) – Chile

2005

- Konstfack (Art Academie) – Stockholm - Sweden

- Lichaamssnoep (Stedelijk Museum CS), Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2006

- Lichaamssnoep (Textile Museum Tilburg), Tilburg - The Netherlands

2019

-‘Odradek, The Making, Unmaking and Remaking of the Elephant’,TallerEloi), Buenos Aires -Argentinian

-‘Odradek, The Making, Unmaking and Remaking of the Elephant’, Museo Caraffa, Cordoba - Argentinian

Residency

2018

-IASPIS Stockholm - Sweden

2016

-Sobrado na Ladeira, Florianopólis - Brazil

-TextilMuseum Tilburg - The Netherlands

2012

-Hans Peter Stiftung, Dusseldorf – Germany

2006

-European Ceramic Work Centre, ‘s-Hertgenbosch - The Netherlands

Public Collections

-Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam - The Netherlands

-Museum Booijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam - The Netherlands

-CODA Museum, Apeldoorn - The Netherlands

-TextielMuseum, Tilburg - The Netherlands

-KunstMuseum Den Haag, The Netherlands

-MAC - Goiás, Goiânia - Brasil

-Coleção da FAV-UFG-Go, Goiânia - Brasil

-Fundação Jaime Camâra - Goiânia - Brasil

-Marzee Collection, Nijmegen - The Netherlands

-Rotasa Trust Collection – USA

Publications (selection)

-’Célio Braga - ARMORED/WOUNDED’, Ernst Van Alphen - Skin.Wound.Queer- KunstMuseum Den Haag, The Netherlands . 2023

-’Remains - Tomorrow: Themes in Contemporary Latin American Abstraction’, Cecilia Fajardo-Hill - Hatje Cantz Publication, 2022

-‘HUID’ (onderdeel van ELEMENTS - Gerd Dierck) ), 2021, Bonnefanten Museum Maastricht - The Netherlands

-‘Célio Braga borduurt over de kwetsbare mens’, 2018 ( Chris Reinewald) – TXP, # 246, Jaargang 62, Winter 2018 - Magazine Over TextielKunst

-‘Beyond the Body’ (Anne Berk), Art Center Silkeborg Bad – Denmark - SBN 978-87-91252-81-5

-‘Cultural Threads - 2017 (Christel Vesters) - TextielMuseum Tilburg - The Netherlands -ISBN/EAN 978-90-70962-64-7

-‘Balin House Projects 10 Years’ – 2017, London - UK - ISBN: 978-0-9956300-0-0

-‘Abluções’, (Hercules Goulart Martins) 2016, Museu Victor Meirelles, Florianópolis - Brasil

-‘Abluções’, (Hercules Goulart Martins / Gilmar Camilo) 2016, MAC-Goiás - Brasil

-‘Multiple Exposure (Ursula Ilse-Newman), The Museum of Arts and Design-MAD-NY, 2014

-‘Nós Afetivos’, Revista Bamboo nr. 40, 10.2014 - Brasil

-‘Threads’ (Mirjan Westen), 2014, Museum Arnhem - The Netherlands

-‘Embraced: Jewellery Sites’, 2011(Anders Ljungberg), Gustavsbergs Konsthall - Sweden -ISBN978-91-978426-5-5

-‘Beyond the Body’ (Anne Berk, Astrid Meyerde, Wolfgang Schäfer), 2012 HPZ Stiftung

-‘Cutting Edges-Contemporary Collages’ (Robert Klanten, Hendrik Heillige, James Gallager), Die Gestalte, Berlin - Germany

-‘EXIT 32’ Estéticas Migratorias: Movimento Double, MIeke Bal (Madrid, 2008)

-‘Items 2’, 2007, ‘Sieraden, over de dingen die voorbijgaan’ (Roelin Plaatsman) - Amsterdam, The Netherlands

-‘Kunstbeeld.nl nr. 5’, 2006 – reviews - pg. 90 ( Wim van der Beek) - The Netherlands

-‘Deliriously’, (2006 - ISBN 90 70680 750) Sharing a Common Skin (Ernst van Alphen)

-‘G.E.B.O.R.D.U.U.R.D, (2006 ISBN 90-70962-37-3) Louise Schouwenberg

-‘Schmuck 2006’, Herausgeber, 2006, München - Duitsland

-‘Itens 1’, January/February 2006, Opsmuk-Jonge Sieraadontwerpers in Nederland.

-‘GZ Art+Design’, Stuttgart (3-2005), Jewelry in a new costume ( Katja Poljanac)

-‘Stedelijk Museum Bulletim (Nr.06, 2004), Loss (Marjan Boot), Amsterdam – The Netherlands

-‘Het Financieele Dagblad’ (13,11,2004), ‘Verwelkende porselein’ (Chris Reinewald)

-‘Loss’, Braga/Eichenberg/Mackert, ISBN 90-809189-1-1 - 2004

-‘Nieuwsbrief NO 83’ - SMBA, Loss, (Marjan Boot)

-‘Tableau’ (26ste Jaargang nr.4 Sep./Okt. 2004), ‘De illusie van het Voorbije’ (Chris Reinewald)

-‘Diario da Manhã’, Goiânia-Brazil (07.31.2004), Panorama da Arte Contemporânea (Ivair Lima)

-‘Marzee Magazine nr 35’, November 2003 - January 2004

-‘Cahier Ravary’ # 18-27 September 2003 - Galerie Marzee

-‘De Telegraaf’, Zaterdag 27 Juli 2002, Hip en oergezellig ( Fiona Hering)

-‘Het PAROOL’, Donderdag 25 Juli 2002, Instant Knus breien is hip ( Pam van der Veen)

-‘Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung,’ 21. April 2002, Nr 16, Auffrisiert Hair Stories-eine Ausstellung in New York (jordan Mejias)

-‘New York Review’, N.Y May 6, 2002, On View: Locks Opening

-‘TimeOut’, New York, May 2-9, 2002, ‘Hair Stories’ (Linda Yablonsky)

-‘Volkskrant’, 22 april 2002, SieraadKunst in de etalage van het Stedelijk (Mieke Zijlmans)

-‘Bulletim Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam,’ 2/2002-Sieraden in Display (Liesbeth den Besten)

-‘Het PAROOL’, Maandag 22 april 2002, Hout en goud in etalage van Stedelijk (Marleen Hengeveld)

-‘DISPLAY-A Proposal for Municipal Art Acquisitions 2000/1’, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

-‘International Textilkunst’, (Marz 2001), Ausstellung im Badisches Landsmuseum Karslruhe

-‘Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung’, Germany(24.01.2001), Alles im Griff dem stinkenden Schiff

-‘Felt/Art’, Crafts and Design, Arnoldsche Art Publishers.2000, Peter Schmitt

-‘Gazetta’, Goiânia - Brasil (May 2000), ‘Diversas faces do desejo’

-‘O Popular’, Goiânia -Brasil (May 2000), ‘Sexo e misticismo na arte contemporânea’

Brazil

Lives and works in Amsterdam (The Netherlands) and São Paulo (Brazil)

Education

1996-2000

Gerrit Rietveld Académie, Amsterdam – The Netherlands

Solo Exhibitions

(selection)

2025

-’Perfect Friends - Perfect Lovers’, Phoebus Rotterdam, The Netherlands

-’ENVIESADO’, Massapê Projects, São Paulo - Brasil

2023

-’SKIN . WOUND . QUEER’, KunstMuseum Den Haag, The Netherlands

2022

-‘Flesh and Flowers’, Galerie Phoebus Rotterdam, The Netherlands

2019

-’80 Bullets’ - Barklund & Co., Stockhom - Sweden

-‘Lama e Arco-Íris Azul e Rosa’ - Galeria Pilar - São Paulo - Brasil

2018

-‘The Years . The Tears . The Rainbow . The Endless Sea - PLATINA Stockholm - Sweden

-‘Field of Flowers’, Phoebus Rotterdam - The Netherlands

2017

-‘White Blur’, Phoebus Rotterdam - The Netherlands

2016

-‘Abluções’, Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Goiás - MAC - Goiânia - Brasil (cat.)

-‘Ablutions’, Museu Victor Meirelles, Florianópolis - Brasil (cat.)

2014

-‘MultiColoridos’, Galeria PIILAR, São Paulo - Brasil

-‘GRID’, Hein Elferink Galerie, Staphorst - The Netherlands

2013

-‘Célio Braga (Solo)’, PINTA Art Fair / Galeria Pilar-SP, London - United Kingdom

2012

-‘Pharmacia Deluxe’, Galeria Amparo 60, Recife - Brasil

-‘Litanies’, Galerie Hein Elferink, Staphorst - The Netherlands

-‘Doloridos.Coloridos’, Galeria PILAR, São Paulo - Brasil

2011

-‘Abstrações para Morrer de Amor’, Galeria da FAV - Goiânia - Brasil

2010

-‘Lacerations’, Galerie Hein Elferink, Staphorst - The Netherlands

2009

-‘Unveil’, Teto Projects, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2008

-‘Caio, Felix, Cuts and Perforations’, Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo – Brasil

2007

-‘Recent Works’ Galerie Hein Elferink, Staphorst, The Netherlands

-‘Possible Jewellery and Related Objects’, Rob Koudijs Galerie, Amsterdam -The Netherlands

2006

-‘B.L.U.E’, BalinHouseProjects, London - England

-Galerie Hein Elferink, Staphorst - The Netherlands

2005

-Galerie van der Mieden, Antwerpen - België

-‘Liquescent’, Platina Gallery, Stockholm - Sweden

2004

- ‘Brancos’, Galerie Louise Smit, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2003

- ‘White Shirts’, HuisRechts, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2000

-‘Objeto desejado (e para sempre) ausente’, MAC-Goiás, Goiânia - Brasil

Group Exhibitions

(selection)

2025

-’HAUS OF FIBER’, TextielMuseum Tilburg - The Netherlands

2024

-’A Summer’s Tale’, Josilda da Conceição Gallery, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2023

-’Un-Solid. Still Being Formed’- Célio Braga & Juliette de Graaf’. Josilda da Conceição Gallery, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2022

-’UNTITLED 1, Célio Braga & Yang Ha’. Josilda da Conceição Gallery, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2021

-‘HUID’, BONNEFANTEN Museum, Maastricht -The Netherlands

-‘DE PEST’, Het Valkhof Museum, Nijmegen - The Netherlands

2019

-‘Verdadero es lo hecho’, Museo José Hernández, Buenos Aires - Argentina

-‘HUID’, Tentoonstelling Zaal Zwijgershoek, Antwerpen - België

-‘Black & White’, TextielMuseum Tilburg - The Netherlands

2018

-‘Cultural Threads’, TextielMuseum Tilburg - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘QUEERMUSEU’, EAV Parque Laje, Rio de Janeiro - Brasil (cat.)

-‘Beyond the Body’, Art Center Silkeborg Ban - Denmark (cat.)

2017

-‘EVOÉ’, Galeria Amparo 60 - Recife, Brasil

-‘QUEERMUSEU’, Satander Cultural, Porto Alegre – Brasil (cat.)

-‘HIGHLY VOLATILE’, Vishal Haarlem – The Netherlands

2016

-’TUDO JOIA’, Bergamin & Gomide, São Paulo, Brasil

2015

-‘Born of Concentration’, RAM Foundation Rotterdam - The Netherlands

-‘Under the Skin’, Textile Museum Tilburg - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘Fashion & Mortality’, Lentos Museum Linz - Áustria (cat.)

2014

-‘O que ainda não é’, Galpão TAC, Rio de Janeiro - Brasil

-‘Threads’, Museum voor Moderne Kunst Arnhem - The Netherlands (cat.)

2012

-‘Beyond the Body’, WELTKUNSTZIMMER, Dusseldorf - Germany (cat.)

2011

-‘Us, in Flux’, Lawrimore Project / Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle - USA. (cat.)

-‘ONTKETEND’, Museum voor Modern Kunst, Arnhem - The Netherlands

-‘Drawing Now Staphorst’, Galerie Hein Elferink, Staphorst - The Netherlands

-‘Salon du Dessin Contemporaine’/Galerie Hein Elferink, Paris - France

-‘PULSE Art Fair’/Sienna Gallery, New York - USA.

-‘EMBRACED’, GustavsBergs Konsthall - Sweden (cat.)

2010

-‘THINK TWICE’, MAD-Museum of Arts and Design, New York - USA

2009

-‘SLASH - Paper Under the Knife’ (cat.), Museum of Arts and Design, New York - USA

-‘Start’, Galerie Hein Elferink, Staphorst - The Netherlands

2008

-‘Papier Biënnale 2008’, Museum Rijswijk - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘SOFT (Autonomous Textiles)’, LandsMuseum, Linz - Austrian

2007

-‘Licht’, RC de Ruimte , Ijmuiden - The Netherlands

-‘Hard Candies’, Motive Gallery, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

-‘GlassWear’, Toledo Museum of Art - U.S.A / SchmuckMuseum Pforzheim - Germany (cat.)

-‘Act//’, Huisrechts, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

-‘Fragmentos do Corpo’, Galeria da FAV, Goiânia, - Brasil (cat.)

-‘Focus 4’, KCO CultuurSalon, Zwolle - The Netherlands

-‘2MOVE: Double movement’, Sala Verónicas-Centro Párraga, Murcia – Spain / ZuiderzeeMuseum, Enkhuizen - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘Brazil Art Lounge’, TAC Eindhoven - The Netherlands

-‘.G.E.B.O.R.D.U.U.R.D.’, TextilMuseum, Tilburg - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘Schmuck 2006’, Internationalen Handwerksmesse München - Germany / Museum of Arts and Design, New York - U.S.A

2005

-‘Bock mit Inhalt’, Stedelijk Museum CS, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2004

-‘LOSS’, Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘Doações MAC 1999-2004’, Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Goiás, Goiânia - Brasil

-‘Oogstrelend Schoon’, CODA-Apeldoorns Museum - The Netherlands

-‘Solo’, Galerie Marzee, Nijmegen - The Netherlands

2003

-‘Ravary Project’, Galerie Marzee, Nijmegen - The Netherlands

-‘BLUR, The Bluring of Categories in the Applied Arts’, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam -The Netherlands

2002

-‘FRAU WILLHELM’, Fanshop Amsterdam - The Netherlands

-‘Nature and Time - International Jewelery Competition’, Deutsches Goldschmiedhaus, Hanau – Germany (cat.)

-‘Hair Stories’, Adam Baumgold Gallery, New York - USA

-‘Beziehungen’, Nederlandse Bank, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

-‘DISPLAY’, A Proposal for Municipal Art Acquisitions-2000/2001, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘FILZ FELT’, Landsmunseum für Vorgeschichte Dresden – Germany / Deutsches Textilmuseum Krefeld - Germany (cat.)

2001

-‘SIERADEN’, The Choice of Apeldoorn, Van Reekum Museum, Apeldoorn - The Netherlands / Badisches Landesmuseum Kalsruhe - Germany (cat.)

2000

-‘Eindexamententoonstelling’ - Kunstpaviljoen, Nieuw-Roden - The Netherlands

-‘Annual International Graduation Show’, Galerie Marzee, Nijmegen - The Netherlands (cat.)

-‘HAUTNAH’, Kunsthalle, Wien - Áustria

1998

-SBK Ijmond-Noord, Beverwijk - The Netherlands

1993

-‘Bienal do Incomum’, Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Goiânia - Brasil (cat.)

1990

-‘Fragments/Wholeness’, Ariel Gallery, New York - USA

Performances

2010

-’Full Blown/Walking on Flowers’, De Oude Kerk Amsterdam/MuseumNacht 11 - The Netherlands

2009

-‘Similitude’ (with Rose Akras), Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo - Brasil

2008

-‘7 maneiras…’ (with Rose Akras)/VERBO, Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo - Brasil

2002

-‘A self Portrait with many faces’ (with Antonio P. de Souza), De BrakkeGrond, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2001

-‘Natural Diversity’ (with Antonio P. de Souza), The Veem Theatre Amsterdam - The Netherlands

Prizes/Subsidies

2008

-Basisstipendium, Fonds BKVB, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2004

-Startstipendium, Fonds BKVB, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2002

-Startstipendium, Fonds BKVB, Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2000

-Marzeer Prize, Nijmegen - The Netherlands

Workshops

2015

- The Skin I Live in (Centro Cultural Valparaiso) – Chile

2005

- Konstfack (Art Academie) – Stockholm - Sweden

- Lichaamssnoep (Stedelijk Museum CS), Amsterdam - The Netherlands

2006

- Lichaamssnoep (Textile Museum Tilburg), Tilburg - The Netherlands

2019

-‘Odradek, The Making, Unmaking and Remaking of the Elephant’,TallerEloi), Buenos Aires -Argentinian

-‘Odradek, The Making, Unmaking and Remaking of the Elephant’, Museo Caraffa, Cordoba - Argentinian

Residency

2018

-IASPIS Stockholm - Sweden

2016

-Sobrado na Ladeira, Florianopólis - Brazil

-TextilMuseum Tilburg - The Netherlands

2012

-Hans Peter Stiftung, Dusseldorf – Germany

2006

-European Ceramic Work Centre, ‘s-Hertgenbosch - The Netherlands

Public Collections

-Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam - The Netherlands

-Museum Booijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam - The Netherlands

-CODA Museum, Apeldoorn - The Netherlands

-TextielMuseum, Tilburg - The Netherlands

-KunstMuseum Den Haag, The Netherlands

-MAC - Goiás, Goiânia - Brasil

-Coleção da FAV-UFG-Go, Goiânia - Brasil

-Fundação Jaime Camâra - Goiânia - Brasil

-Marzee Collection, Nijmegen - The Netherlands

-Rotasa Trust Collection – USA

Publications (selection)

-’Célio Braga - ARMORED/WOUNDED’, Ernst Van Alphen - Skin.Wound.Queer- KunstMuseum Den Haag, The Netherlands . 2023

-’Remains - Tomorrow: Themes in Contemporary Latin American Abstraction’, Cecilia Fajardo-Hill - Hatje Cantz Publication, 2022

-‘HUID’ (onderdeel van ELEMENTS - Gerd Dierck) ), 2021, Bonnefanten Museum Maastricht - The Netherlands

-‘Célio Braga borduurt over de kwetsbare mens’, 2018 ( Chris Reinewald) – TXP, # 246, Jaargang 62, Winter 2018 - Magazine Over TextielKunst

-‘Beyond the Body’ (Anne Berk), Art Center Silkeborg Bad – Denmark - SBN 978-87-91252-81-5

-‘Cultural Threads - 2017 (Christel Vesters) - TextielMuseum Tilburg - The Netherlands -ISBN/EAN 978-90-70962-64-7

-‘Balin House Projects 10 Years’ – 2017, London - UK - ISBN: 978-0-9956300-0-0

-‘Abluções’, (Hercules Goulart Martins) 2016, Museu Victor Meirelles, Florianópolis - Brasil

-‘Abluções’, (Hercules Goulart Martins / Gilmar Camilo) 2016, MAC-Goiás - Brasil

-‘Multiple Exposure (Ursula Ilse-Newman), The Museum of Arts and Design-MAD-NY, 2014

-‘Nós Afetivos’, Revista Bamboo nr. 40, 10.2014 - Brasil

-‘Threads’ (Mirjan Westen), 2014, Museum Arnhem - The Netherlands

-‘Embraced: Jewellery Sites’, 2011(Anders Ljungberg), Gustavsbergs Konsthall - Sweden -ISBN978-91-978426-5-5

-‘Beyond the Body’ (Anne Berk, Astrid Meyerde, Wolfgang Schäfer), 2012 HPZ Stiftung

-‘Cutting Edges-Contemporary Collages’ (Robert Klanten, Hendrik Heillige, James Gallager), Die Gestalte, Berlin - Germany

-‘EXIT 32’ Estéticas Migratorias: Movimento Double, MIeke Bal (Madrid, 2008)

-‘Items 2’, 2007, ‘Sieraden, over de dingen die voorbijgaan’ (Roelin Plaatsman) - Amsterdam, The Netherlands

-‘Kunstbeeld.nl nr. 5’, 2006 – reviews - pg. 90 ( Wim van der Beek) - The Netherlands

-‘Deliriously’, (2006 - ISBN 90 70680 750) Sharing a Common Skin (Ernst van Alphen)

-‘G.E.B.O.R.D.U.U.R.D, (2006 ISBN 90-70962-37-3) Louise Schouwenberg

-‘Schmuck 2006’, Herausgeber, 2006, München - Duitsland

-‘Itens 1’, January/February 2006, Opsmuk-Jonge Sieraadontwerpers in Nederland.

-‘GZ Art+Design’, Stuttgart (3-2005), Jewelry in a new costume ( Katja Poljanac)

-‘Stedelijk Museum Bulletim (Nr.06, 2004), Loss (Marjan Boot), Amsterdam – The Netherlands

-‘Het Financieele Dagblad’ (13,11,2004), ‘Verwelkende porselein’ (Chris Reinewald)

-‘Loss’, Braga/Eichenberg/Mackert, ISBN 90-809189-1-1 - 2004

-‘Nieuwsbrief NO 83’ - SMBA, Loss, (Marjan Boot)

-‘Tableau’ (26ste Jaargang nr.4 Sep./Okt. 2004), ‘De illusie van het Voorbije’ (Chris Reinewald)

-‘Diario da Manhã’, Goiânia-Brazil (07.31.2004), Panorama da Arte Contemporânea (Ivair Lima)

-‘Marzee Magazine nr 35’, November 2003 - January 2004

-‘Cahier Ravary’ # 18-27 September 2003 - Galerie Marzee

-‘De Telegraaf’, Zaterdag 27 Juli 2002, Hip en oergezellig ( Fiona Hering)

-‘Het PAROOL’, Donderdag 25 Juli 2002, Instant Knus breien is hip ( Pam van der Veen)

-‘Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung,’ 21. April 2002, Nr 16, Auffrisiert Hair Stories-eine Ausstellung in New York (jordan Mejias)

-‘New York Review’, N.Y May 6, 2002, On View: Locks Opening

-‘TimeOut’, New York, May 2-9, 2002, ‘Hair Stories’ (Linda Yablonsky)

-‘Volkskrant’, 22 april 2002, SieraadKunst in de etalage van het Stedelijk (Mieke Zijlmans)

-‘Bulletim Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam,’ 2/2002-Sieraden in Display (Liesbeth den Besten)

-‘Het PAROOL’, Maandag 22 april 2002, Hout en goud in etalage van Stedelijk (Marleen Hengeveld)

-‘DISPLAY-A Proposal for Municipal Art Acquisitions 2000/1’, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

-‘International Textilkunst’, (Marz 2001), Ausstellung im Badisches Landsmuseum Karslruhe

-‘Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung’, Germany(24.01.2001), Alles im Griff dem stinkenden Schiff

-‘Felt/Art’, Crafts and Design, Arnoldsche Art Publishers.2000, Peter Schmitt

-‘Gazetta’, Goiânia - Brasil (May 2000), ‘Diversas faces do desejo’

-‘O Popular’, Goiânia -Brasil (May 2000), ‘Sexo e misticismo na arte contemporânea’

04/

Photo’s credit

Clemens

Boon

Josefina Elkenaar

Peter Gerritsen

Cris Bierrenbach

Fernanda Figueiredo

Henk Nieman

Paulo Dourado Rezende

Ding Musa

Remco Veenbrik

Simon Pillaud

Bas Czerwinski

Josefina Elkenaar

Peter Gerritsen

Cris Bierrenbach

Fernanda Figueiredo

Henk Nieman

Paulo Dourado Rezende

Ding Musa

Remco Veenbrik

Simon Pillaud

Bas Czerwinski

Célio Braga ©2022

23/

CÉLIO BRAGA:

CUIDADO COM A PINTURA

CELSO FIORAVANTE

Célio Braga: Cuidado com a Pintura

A exposição “Célio Braga: Cuidado com a Pintura” apresenta a produção recente do artista mineiro Célio Braga (Guimarânia, MG, 1963). São pinturas recentes, mas atemporais. São pequenos formatos, mas que crescem ao olhar do espectador, pois trabalham com nuances e detalhes, sugerem dúvidas e mistérios maiores. As pequenas pinturas de Célio Braga não cabem em si. Elas subvertem significantes e significados. Uma gota é mais que uma gota. Um cravo é mais que um cravo. Um círculo é mais que um círculo.

Guimarânia, Goiânia, Nova York, Amsterdã, São Paulo, Guimarânia... Sua pintura viaja dos grotões e veredas às metrópoles para tratar de questões que são individuais e universais, como a pele como simulacro da passagem do tempo e da persistência da memória, e o corpo atravessado por dilemas e sonhos.

Célio Braga prepara a sua tela. Pinta e repinta o linho ali quase branco, esticado, inerte, submisso, silencioso, passivo. Pequenos retalhos recortados em formas ora abstratas ora figurativas ocupam o espaço. São tecidos, pintados, colados, bordados, afogados em cera, lixados... Formas que lutam por um olhar que lhes dê vida no big bang daquele pequeno universo em ebulição, frágil e transitório. Célio Braga é o cavalo de suas pinturas. Ele está sendo usado por elas.

Distante anos-luz das modas estéticas, Braga tece sua produção com linguagens ancestrais, como o bordado, a escultura e a performance. No atelier, só com a sua arte, tinta e linhas escorrem como as lágrimas de uma vela que caminha em direção ao fim.

O artista pesca suas referências na arte popular, contemporânea e conceitual. O experimentalismo e a liberdade de Paul Klee, a força ética e autobiográfica de Louise Bourgeois, a política e a poética de Félix González-Torres, a coerência e o minimalismo de Agnes Martin, e a intensidade e a delicadeza de Leonilson são referências reconhecidas pelo artista, mas a fluidez de sua produção segue aberta a quem mais chegar, a todos que vejam a arte como uma forma de oração.

Celso Fioravante

A exposição “Célio Braga: Cuidado com a Pintura” apresenta a produção recente do artista mineiro Célio Braga (Guimarânia, MG, 1963). São pinturas recentes, mas atemporais. São pequenos formatos, mas que crescem ao olhar do espectador, pois trabalham com nuances e detalhes, sugerem dúvidas e mistérios maiores. As pequenas pinturas de Célio Braga não cabem em si. Elas subvertem significantes e significados. Uma gota é mais que uma gota. Um cravo é mais que um cravo. Um círculo é mais que um círculo.

Guimarânia, Goiânia, Nova York, Amsterdã, São Paulo, Guimarânia... Sua pintura viaja dos grotões e veredas às metrópoles para tratar de questões que são individuais e universais, como a pele como simulacro da passagem do tempo e da persistência da memória, e o corpo atravessado por dilemas e sonhos.

Célio Braga prepara a sua tela. Pinta e repinta o linho ali quase branco, esticado, inerte, submisso, silencioso, passivo. Pequenos retalhos recortados em formas ora abstratas ora figurativas ocupam o espaço. São tecidos, pintados, colados, bordados, afogados em cera, lixados... Formas que lutam por um olhar que lhes dê vida no big bang daquele pequeno universo em ebulição, frágil e transitório. Célio Braga é o cavalo de suas pinturas. Ele está sendo usado por elas.

Distante anos-luz das modas estéticas, Braga tece sua produção com linguagens ancestrais, como o bordado, a escultura e a performance. No atelier, só com a sua arte, tinta e linhas escorrem como as lágrimas de uma vela que caminha em direção ao fim.

O artista pesca suas referências na arte popular, contemporânea e conceitual. O experimentalismo e a liberdade de Paul Klee, a força ética e autobiográfica de Louise Bourgeois, a política e a poética de Félix González-Torres, a coerência e o minimalismo de Agnes Martin, e a intensidade e a delicadeza de Leonilson são referências reconhecidas pelo artista, mas a fluidez de sua produção segue aberta a quem mais chegar, a todos que vejam a arte como uma forma de oração.

Celso Fioravante

22/

PORTRAIT

Geschreven en gelezen door Liesbeth den Besten bij de opening van de tentoonstelling Perfect Friends – Perfect Lovers in Phoebus Rotterdam.

Liesbeth den Besten

Ik heb Célio Braga leren kennen bij zijn afstuderen op de Rietveld Academie – nu 25 jaar geleden. Zijn werk viel op tussen het werk van zijn collega’s. Hij had als ik het me goed herinner midden in een klaslokaal een kamertje gebouwd waar je in kon stappen. Binnenin kwam je ogen tekort. Het was een klein kamertje met een enorme expressie, een heiligdom waarvan de wanden beschilderd waren, en gedeeltelijk van was – het rook er op een speciale manier. De wanden waren volgehangen met allerlei dingen, votieven, memorabilia, en ook halssieraden van textiel en glaskralen. Het werk maakte indertijd enorme indruk op mij. Je stapte een andere wereld in, een heel eigen en on-Hollandse wereld, die om aandacht en bezinning vroeg.

Foto’s zijn er niet van gemaakt, niet door Celio, en niet door mij. Het was het Pre-Digitale Tijdperk, maar ik ben blij met mijn herinneringen, die zijn mij goud waard.

Célio is in 1965 geboren op het Braziliaanse platteland, zo’n 10 uur met de bus van Sao Paolo - waar hij sinds zijn afstuderen de helft van het jaar woont (de andere helft woont hij in Amsterdam). Toen hij afstudeerde op de Rietveld Academie had hij al een hele weg afgelegd in de kunst: via academies in Sao Paolo en Boston (USA) waar hij schilderkunst studeerde, kwam hij in 1996 dankzij Dennis naar Amsterdam om textiel te studeren aan de Rietveld Academy. Na een jaar stapte hij over naar de sieradenafdeling waar hij les had van een fantastisch team docenten Ruudt Peters, Iris Eichenberg, en Marjan Unger.

Toch staat werken met metaal hem tegen en heeft hij nooit gesmede sieraden gemaakt. Het was de aandacht op de afdeling sieraden voor de mens en het lichaam die hem aantrokken. Hij houdt van zachte materialen, materialen die de huid aangeraakt hebben, hemden, lakens, zakdoeken. Een tijdlang werd hij omarmd door de sieradenwereld en exposeerde in de sieradengalerie van Louise Smit. Maar dat jasje paste hem niet.

Over de objecten van textiel, glaskralen en menselijk haar, die hij zo rond 2008 maakte schreef ik eens het volgende:

“ze zijn met de hand gestikt, zorgvuldig, minuut na minuut, uur na uur, in een soort ritueel continuüm. Dit is devotie, toewijding, vergelijkbaar met de manier waarop middeleeuwse monniken zich wijden aan de verluchting van manuscripten.”

Ik vroeg me af wat deze abstracte objecten in een sieradengalerie deden. Moest men ze dragen of niet en zo ja, waar was dan de speld? Hij erkent nu dat hij toen een zekere weerstand tegen sieraden had en dat hij de mensen een beetje wilde plagen, ze een keus wilde laten maken, wil je een object of wil je het kunnen dragen als sieraad. Daar had hij spelden voor maar uiteindelijk werkte het niet echt goed.

Célio was veel breder georiënteerd, hij deed performances, installaties, snijdsels in papier. Hij maakte een intense video, twee video’s tegenover elkaar geplaatst waar de kijker tussen stond, van zijn moeder van heel dichtbij gefilmd na het overlijden van haar dochter – a woman of sorrows. Een intiem portret dat ook in mijn geheugen gegrift staat.

Maar toch komt hij altijd weer bij textiel en borduren en stikken terug. Hij kan met naald en draad beeldhouwen – wat tweedimensionaal en alledaags is een vorm geven, een vorm die in niets meer herinnert aan de oorsprong van het object.

Célio werkte voor het eerst met witte overhemden in 2001-2002, vlak na zijn afstuderen.

Dankzij de introductie van een medicatie die HIV kon stoppen was er een eind aan de AIDS-crisis gekomen. Na een periode van ongeveer 20 jaar waarin de ziekte vreselijke sporen had nagelaten was de angst nog niet voorbij. Célio vroeg zijn vrienden om oude gedragen witte overhemden. Door middel van vouwen, stikken en borduren perste hij ze samen tot langwerpige organische vormen met kleine uitstulpingen en holtes. En met een geborduurde huid, een ragfijn netwerk van borduursels, die als een zich openende cocon gedeeltelijk om de vormen heen zit. Zo ontstond een intrigerende installatie van 28 hangende objecten die associaties met lichamen opriepen – de installatie is in 2023 nog tentoongesteld in Kunstmuseum Den Haag op zijn solotentoonstelling. Je zou ze kunnen zien als amuletten, bezielde beschermende pantsers tegen de kwade buitenwereld. Ze toonden zijn onvoorwaardelijke liefde voor zijn vrienden.

En nu zijn wij hier in zijn tentoonstelling Perfect Friends – Perfect Lovers, en zien we een serie van tientallen ongebruikelijke abstracte portretten van textiel. Ze zijn gemaakt van gedragen en geschonken overhemden van vrienden uit verschillende landen. Hij snijdt de hemden in repen en daarna weeft hij de stroken tot een rechthoek, vervolgens worden de onderdelen met de hand aan elkaar gestikt. Ook knoopjes, knoopsgaten, boordjes, en soms logos, worden meegenomen in het werk maar het is het fragiele samenbindende stiksel dat de aandacht vraagt. Elk hemd leidde tot een andere bewerking, minutieus genaaid met naald en draad en aandacht voor degene van wie het overhemd afkomstig is. Hij bewerkt het textiel zodanig dat het op een huid gaat lijken, en een persoonlijkheid krijgt. Hij stopt zijn eigen bezieling erin maar ook die van zijn vrienden. Ze dragen de namen van die vrienden en vriendenstellen. De maten van de portretten zijn klein en allemaal gelijk, ze hebben de menselijke maat. Ze tonen een andere mannelijkheid, de band en liefde tussen mannen.

De serie is een prachtige hommage aan de man.

Liesbeth den Besten, Rotterdam 7 september 2025

Foto’s zijn er niet van gemaakt, niet door Celio, en niet door mij. Het was het Pre-Digitale Tijdperk, maar ik ben blij met mijn herinneringen, die zijn mij goud waard.

Célio is in 1965 geboren op het Braziliaanse platteland, zo’n 10 uur met de bus van Sao Paolo - waar hij sinds zijn afstuderen de helft van het jaar woont (de andere helft woont hij in Amsterdam). Toen hij afstudeerde op de Rietveld Academie had hij al een hele weg afgelegd in de kunst: via academies in Sao Paolo en Boston (USA) waar hij schilderkunst studeerde, kwam hij in 1996 dankzij Dennis naar Amsterdam om textiel te studeren aan de Rietveld Academy. Na een jaar stapte hij over naar de sieradenafdeling waar hij les had van een fantastisch team docenten Ruudt Peters, Iris Eichenberg, en Marjan Unger.

Toch staat werken met metaal hem tegen en heeft hij nooit gesmede sieraden gemaakt. Het was de aandacht op de afdeling sieraden voor de mens en het lichaam die hem aantrokken. Hij houdt van zachte materialen, materialen die de huid aangeraakt hebben, hemden, lakens, zakdoeken. Een tijdlang werd hij omarmd door de sieradenwereld en exposeerde in de sieradengalerie van Louise Smit. Maar dat jasje paste hem niet.

Over de objecten van textiel, glaskralen en menselijk haar, die hij zo rond 2008 maakte schreef ik eens het volgende:

“ze zijn met de hand gestikt, zorgvuldig, minuut na minuut, uur na uur, in een soort ritueel continuüm. Dit is devotie, toewijding, vergelijkbaar met de manier waarop middeleeuwse monniken zich wijden aan de verluchting van manuscripten.”

Ik vroeg me af wat deze abstracte objecten in een sieradengalerie deden. Moest men ze dragen of niet en zo ja, waar was dan de speld? Hij erkent nu dat hij toen een zekere weerstand tegen sieraden had en dat hij de mensen een beetje wilde plagen, ze een keus wilde laten maken, wil je een object of wil je het kunnen dragen als sieraad. Daar had hij spelden voor maar uiteindelijk werkte het niet echt goed.

Célio was veel breder georiënteerd, hij deed performances, installaties, snijdsels in papier. Hij maakte een intense video, twee video’s tegenover elkaar geplaatst waar de kijker tussen stond, van zijn moeder van heel dichtbij gefilmd na het overlijden van haar dochter – a woman of sorrows. Een intiem portret dat ook in mijn geheugen gegrift staat.

Maar toch komt hij altijd weer bij textiel en borduren en stikken terug. Hij kan met naald en draad beeldhouwen – wat tweedimensionaal en alledaags is een vorm geven, een vorm die in niets meer herinnert aan de oorsprong van het object.

Célio werkte voor het eerst met witte overhemden in 2001-2002, vlak na zijn afstuderen.

Dankzij de introductie van een medicatie die HIV kon stoppen was er een eind aan de AIDS-crisis gekomen. Na een periode van ongeveer 20 jaar waarin de ziekte vreselijke sporen had nagelaten was de angst nog niet voorbij. Célio vroeg zijn vrienden om oude gedragen witte overhemden. Door middel van vouwen, stikken en borduren perste hij ze samen tot langwerpige organische vormen met kleine uitstulpingen en holtes. En met een geborduurde huid, een ragfijn netwerk van borduursels, die als een zich openende cocon gedeeltelijk om de vormen heen zit. Zo ontstond een intrigerende installatie van 28 hangende objecten die associaties met lichamen opriepen – de installatie is in 2023 nog tentoongesteld in Kunstmuseum Den Haag op zijn solotentoonstelling. Je zou ze kunnen zien als amuletten, bezielde beschermende pantsers tegen de kwade buitenwereld. Ze toonden zijn onvoorwaardelijke liefde voor zijn vrienden.

En nu zijn wij hier in zijn tentoonstelling Perfect Friends – Perfect Lovers, en zien we een serie van tientallen ongebruikelijke abstracte portretten van textiel. Ze zijn gemaakt van gedragen en geschonken overhemden van vrienden uit verschillende landen. Hij snijdt de hemden in repen en daarna weeft hij de stroken tot een rechthoek, vervolgens worden de onderdelen met de hand aan elkaar gestikt. Ook knoopjes, knoopsgaten, boordjes, en soms logos, worden meegenomen in het werk maar het is het fragiele samenbindende stiksel dat de aandacht vraagt. Elk hemd leidde tot een andere bewerking, minutieus genaaid met naald en draad en aandacht voor degene van wie het overhemd afkomstig is. Hij bewerkt het textiel zodanig dat het op een huid gaat lijken, en een persoonlijkheid krijgt. Hij stopt zijn eigen bezieling erin maar ook die van zijn vrienden. Ze dragen de namen van die vrienden en vriendenstellen. De maten van de portretten zijn klein en allemaal gelijk, ze hebben de menselijke maat. Ze tonen een andere mannelijkheid, de band en liefde tussen mannen.

De serie is een prachtige hommage aan de man.

Liesbeth den Besten, Rotterdam 7 september 2025

21/

ENVIESADO

Tálisson Melo

Aos 19 anos, no centro de Madri, dediquei uma manhã a passar por lojas de roupas sociais masculinas. Muitas calças pretas e camisas brancas, alguns tons de azul, cinza e marrom formavam uma paisagem sem sobressaltos. A missão era fazer jus ao investimento da minha mãe ao me mandar dinheiro para comprar uma "roupa melhorzinha” já que eu receberia congratulaciones em um evento público na universidade. Busquei uma camisa confortável e barata, mas que poderia “imprimir bem” a seriedade merecedora de honraria. Vestindo a camisa escolhida, a sensação era de que minha pele se fundia com o tecido da roupa e algo em mim se transformava para sempre (?!)… De lá para cá, usei essa camisa por não mais que quatro vezes até meus 26 anos. A guardei inútil no cabide até hoje, o fato de que ainda me caia bem revela uma fôrma persistente em relação ao meu corpo mais adulto.

Agora, aos 34 anos, escrevendo este texto para a exposição de Célio Braga — que decidimos intitular de enviesado —, me conformo com a ideia de entregar a seus cuidados essa camisa carregada de uma memória singular da ritualização de certa masculinidade/civilidade. Sei que essa camisa será desconstruída em rasgos e cortes a serem esticados e enrolados sobre um chassi de madeira, criando um dos 14 retratos têxteis da série perfect friends - perfect lovers. Cada retrato parte dessa mesma operação de desfazer camisas também dadas por homens com quem Célio mantém alguma relação — são amigos, amantes, companheiros, colegas, conhecidos, pais, filhos, irmãos, sobrinhos, mais jovens e mais velhos, brasileiros, estrangeiros, heterossexuais, bissexuais, homossexuais… Depois, o ato de reconstruí-las por meio da costura e bordado em outra configuração, sobre módulos retangulares de 35 x 30 cm. As distintas cores, padronagens, tipos de tecidos e detalhes como pences, pregas, bolsos, carcelas, etiquetas, botões e casas projetam os aspectos próprios de cada retrato.

Célio trabalha sobre coisas ancoradas em memórias de uso, algo que vai tão junto da pele, a cobrindo e protegendo, mas, principalmente, servindo como fôrma do que já está no mundo agindo sobre o corpo e da maneira como o corpo se coloca no mundo. Há ainda o gesto de desapego em doá-las, de algum modo ligado a despir-se e deixar-se ser tocado, algo próprio das variadas relações entre homens que o conjunto reencena pela presença óbvia do toque, de se poder ver o artista habitar nesses corpos pela pele, do avesso. A pele como matéria mediadora que funde eu e o mundo — “be matter itself!”.[1]

Trabalhos anteriores de Célio trazem a pele fotografada e impressa em papel, que ele perfura e sutura, salientando sua porosidade e permeabilidade como prolongação indistinta entre dentro e fora, das e nas relações, trocas e afetações.[2]Ao destruir as camisas e enquadrar seus fragmentos em outra ordenação para, então, costurá-las de novo, bordando meticulosamente as partes que se sobrepõem e se emaranham, a ação criativa de Célio se dá por horas em um corpo a corpo cheio de impulsos e cálculos, uma negociação constante com os materiais, com seu desejo, sua técnica e seu próprio corpo em trabalho.

Ao conhecer mais sobre a trajetória pessoal e artística de Célio e passar a fazer parte do processo em que vem construindo esses retratos imperfeitos de amigos-amantes, retomei as indagações que Michel Foucault devolvera ao ser entrevistado, em 1981, acerca do modo de vida homossexual:[3]

Quais relações podem ser estabelecidas, inventadas, multiplicadas, moduladas através da homossexualidade?

Como é possível para homens estarem juntos? Viver juntos, compartilhar seus tempos, suas refeições, seus quartos, seus lazeres, suas aflições, seus saberes, suas confidências?

O que é isso de estar entre homens, "despidos", fora das relações institucionais, de família, de profissão, de companheirismo obrigatório?

A resposta aberta à sua própria pergunta indica a possibilidade de se reimaginar as relações, a amizade, a intimidade e a vida comunitária. Isso aparece com muita força no trabalho de Célio. Esse desejo-inquietação convida a se reinventar relações variáveis, individualmente moduladas, ainda sem fôrmas, que se projetam para além do ato sexual entre homens ou da ideia de fusão amorosa das identidades — assim, cada retrato vai se fazendo e ganha o nome de quem vestia a peça de roupa desconstruída. Estabelecer um modo de vida homossexual, introduzindo o prazer e o amor onde só se via a lei, a regra ou o hábito, é o que perturba a lógica tradicional da família nuclear e a heteronormatividade. Esse conjunto de retratos bordados pode ser visto como materialização das diversas possibilidades de se tramar relações, construir formas únicas e maleáveis de contatos e conexões com outros homens. Na urdidura do cuidado, do prazer, da intimidade, ética, cumplicidade, companheirismo, erotismo e desejo, as peças evidenciam rearranjos relativamente reversíveis, abertos a outras reconfigurações:

A homossexualidade é uma ocasião histórica de reabrir virtualidades relacionais e afetivas, não tanto pelas qualidades intrínsecas do homossexual, mas pela posição de "enviesado", de alguma forma, as linhas diagonais que ele pode traçar no tecido social, as quais permitem fazer aparecerem essas virtualidades.

Com a fôrma das camisas sociais e com os gestos de ajustá-las e abotoá-las, imagens de um corpo disciplinado rotinizam o estereótipo de masculinidade associado à racionalidade, autoridade, higiene, assepsia, seriedade, profissionalismo, ordem e controle. As camisas brancas de punhos estreitos, em particular, enfatizavam a uniformização de uma identidade coletiva masculina associada ao “neutro”, ao “universal”, valores associados à performance hegemônica de gênero, classe e raça na sociedade burguesa desde pelo menos meados do século XIX.[4] Já contamos com uma história da relação entre moda e cultura queer permeada por expressões de inconformação polivalentes, a apropriação das camisas nas festas, ruas e passarelas afirmam a artificialidade das ordenações binárias do feminino e do masculino, gerando outras configurações, às vezes tão radicais que abalam até mesmo a noção de uma fôrma humana. No entanto, as camisas convencionais empregadas por Célio nesses trabalhos recentes chamam mais atenção para a manutenção dessa fôrma de corpos masculinos, os interstícios ambíguos entre adequação, repressão, docilidade e esconderijo de um lado, e erotismo, despojamento e ironia camp, do outro. Com a desconstrução de cada uma e sua reconstrução “enviesada”, nas direções oblíquas das relações vivas, emerge o desalinho, o entortado, o inadequado.

Em jogo com as casas desabotoadas, alguns buracos e falhas na cobertura da quase-superfície se fazem às vezes mais ou menos evidentes, porém, sempre ruidosos ao olhar mais atento e aproximado. Nitidamente propositais, essas lacunas permitem cada retrato respirar e palpitar na iminência de serem desfeitos novamente ou alterados por mais emendas, outras camadas de pano, alguma pele ou corpo que se interponha ali, antes da parede. A mesma coisa acontece com as sobras ou dobras que se desprendem do retângulo ou do plano como abscessos, apêndices, cicatrizes ou tentáculos. Seriam pistas de um desinteresse ao enquadramento absoluto, evidência da vontade de transbordamento em que cada relação implica. Ambos elementos reforçam o desapego pelo acabamento, o esmero objetivado no bordado também ostenta o erro, o desvio, o remendo e as correções mal-sucedidas, indícios das negociações em termos nunca totalmente sem atritos ou opacidades, entre corpo-mente e objeto-matéria, entre eu e outro — como no que se vive em relação.

A historiadora de arte e psicanalista Rozsika Parker[5] mapeou o processo histórico de declínio do status do bordado do fim da Idade Média até sua consolidação na constelação das “artes menores”. Também no século XIX, com a divisão arte/artesanato, o bordado passava de uma forma de arte elevada praticada por homens e mulheres, particularmente na Inglaterra, para ser visto como ofício inferior e feminino marginalizado ao âmbito doméstico, do que é feito por mulheres e “por amor”. Isso coloca a prática de bordar como central na afirmação de uma ideologia hegemônica da feminilidade. Parker aponta para os dados de pesquisas realizadas no final dos anos 1970 — quando se afirmava que “o bordado é o passatempo preferido de 2% dos homens britânicos, mais ou menos a mesma quantidade daqueles que frequentam a igreja regularmente”. Ela mostra a permanência desse estereótipo e as assimetrias embutidas no interior da divisão sexual do trabalho: “só maricas e mulheres costuram e vão a cultos”.[6]

Mais recentemente, o historiador Joseph McBrinn,[7] e em diálogo direto com Parker, analisa o papel do bordado na criação e subversão da masculinidade: embora se tenha registros da presença do bordado na educação básica de meninos da classe operária no século XIX para acalmá-los; bem como nas dinâmicas tradicionais de ócio dos marinheiros que bordavam presentes para entes queridos sem terem abalada a hipermasculinidade associada a sua profissão; um dos efeitos da centralidade do bordado na “criação da feminilidade” é sua estigmatização como “efeminante” e sua afirmação como uma espécie de “ousado emblema da auto-identificação queer”. Questionando a rigidez da heteronorma em contexto de criminalização da homossexualidade, homens gays bordaram uma codificação íntima de sua vida sexual e afetiva, até mais tarde se ostentar o bordado na celebração camp das possibilidades de sua existência. Longe de afirmar uma essência feminina, gay, queer, dócil e amorosa sobre o bordado, é ainda possível observar como essa prática meticulosa se afirmou historicamente como símbolo de cuidado e amor, sem deixar de se inscrever como uma reivindicação política ruidosa que vai morando nos detalhes.

Ao ver pronto meu retrato, com minha camisa destruída, manchada e recosturada, levando ainda meu nome como título, reconheço algumas dobras de um passado que ainda cabe no corpo, mas que também passa a se desprender de mim. Umas tantas gramas de pó de gesso infiltrado pela pele, entupindo os poros e endurecendo cada articulação, começasse a se esvair. É como se o gesto de Célio pudesse alcançar a musculatura, os nervos, os tendões, liberando o corpo de uma camisa de força interna. No quadro, desfeita e reconfigurada, a camisa chama mais atenção para tudo o que não se conteve e não se moldou. Ao finalizar cada um dos retratos têxteis de perfect friends - perfect lovers com bordado, o trabalho de Célio Braga apresentado em enviesado se insere nessa trama de reinvenções para existência das relações entre homens e da própria ideia de masculinidade, encenando também a repetição do gesto propositivo que vejo enunciado nos últimos versos de um poema de Camila Sosa Villada[8]:

…

Continuemos a nos amar neste pântano de contradições.

Continuemos a nos dar as mãos na rua,

beijos no trem e abraços na grama.

Continuemos a nos vestir de mulheres,

a nos vestir de homem.

Continuemos a perdoar e a amar,

e não nos afastemos do trabalho lento e eficaz do amor…

mesmo que pareça piegas.

A verdade é que há coisas que deixaram de ser óbvias.

[1] Citação direta de As Tentações de Santo Antão de Gustave Flaubert (1874) inscrita na obra Deliriously (2005).

[2] Ernst van Alphen (2006) evoca a noção de skin ego do psicanalista Didier Anzieu para enfatizar a negação da pele como fronteira absoluta entre indivíduo e o mundo no obra de Célio Braga, abordando-a mais como “conectividades íntimas” para afirmar um corpo vulnerável.

[3] De l'amitié comme mode de vie. Entrevista de Michel Foucault a R. de Ceccatty, J. Danet e J. le

Bitoux, publicada no jornal Gai Pied, nº 25, abril de 1981. Tradução por Wanderson Flor do Nascimento e publicada no site Espaço Michel Foucault (2001).

[4] A relação da moda com os estereótipos de gênero é escrutinada por Joanne Entwistle em The Fashionable Body: Fashion, Dress & Modern Social Theory (2015).

[5] Rozsika Parker. The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (1984).

[6] Sobre a presença do bordado na arte brasileira, com indicação de outras autorias masculinas que o empregaram, ver o catálogo da exposição Transbordar: transgressões do bordado na arte, curada por Ana Paula Simioni no Sesc Pinheiros, São Paulo, com textos de Rosana Paulino e Carmen Cordero Reiman (2020-2021).

[7] Joseph McBrinn. Queering the Subversive Stitch: Men and the Culture of Needlework (2020).

[8] Publicado primeiramente em 2015, o poema foi traduzido do espanhol por Joca Reiners e publicado na coletânea A namorada de Sandro(2024).

Agora, aos 34 anos, escrevendo este texto para a exposição de Célio Braga — que decidimos intitular de enviesado —, me conformo com a ideia de entregar a seus cuidados essa camisa carregada de uma memória singular da ritualização de certa masculinidade/civilidade. Sei que essa camisa será desconstruída em rasgos e cortes a serem esticados e enrolados sobre um chassi de madeira, criando um dos 14 retratos têxteis da série perfect friends - perfect lovers. Cada retrato parte dessa mesma operação de desfazer camisas também dadas por homens com quem Célio mantém alguma relação — são amigos, amantes, companheiros, colegas, conhecidos, pais, filhos, irmãos, sobrinhos, mais jovens e mais velhos, brasileiros, estrangeiros, heterossexuais, bissexuais, homossexuais… Depois, o ato de reconstruí-las por meio da costura e bordado em outra configuração, sobre módulos retangulares de 35 x 30 cm. As distintas cores, padronagens, tipos de tecidos e detalhes como pences, pregas, bolsos, carcelas, etiquetas, botões e casas projetam os aspectos próprios de cada retrato.

Célio trabalha sobre coisas ancoradas em memórias de uso, algo que vai tão junto da pele, a cobrindo e protegendo, mas, principalmente, servindo como fôrma do que já está no mundo agindo sobre o corpo e da maneira como o corpo se coloca no mundo. Há ainda o gesto de desapego em doá-las, de algum modo ligado a despir-se e deixar-se ser tocado, algo próprio das variadas relações entre homens que o conjunto reencena pela presença óbvia do toque, de se poder ver o artista habitar nesses corpos pela pele, do avesso. A pele como matéria mediadora que funde eu e o mundo — “be matter itself!”.[1]

Trabalhos anteriores de Célio trazem a pele fotografada e impressa em papel, que ele perfura e sutura, salientando sua porosidade e permeabilidade como prolongação indistinta entre dentro e fora, das e nas relações, trocas e afetações.[2]Ao destruir as camisas e enquadrar seus fragmentos em outra ordenação para, então, costurá-las de novo, bordando meticulosamente as partes que se sobrepõem e se emaranham, a ação criativa de Célio se dá por horas em um corpo a corpo cheio de impulsos e cálculos, uma negociação constante com os materiais, com seu desejo, sua técnica e seu próprio corpo em trabalho.

Ao conhecer mais sobre a trajetória pessoal e artística de Célio e passar a fazer parte do processo em que vem construindo esses retratos imperfeitos de amigos-amantes, retomei as indagações que Michel Foucault devolvera ao ser entrevistado, em 1981, acerca do modo de vida homossexual:[3]

Quais relações podem ser estabelecidas, inventadas, multiplicadas, moduladas através da homossexualidade?

Como é possível para homens estarem juntos? Viver juntos, compartilhar seus tempos, suas refeições, seus quartos, seus lazeres, suas aflições, seus saberes, suas confidências?

O que é isso de estar entre homens, "despidos", fora das relações institucionais, de família, de profissão, de companheirismo obrigatório?

A resposta aberta à sua própria pergunta indica a possibilidade de se reimaginar as relações, a amizade, a intimidade e a vida comunitária. Isso aparece com muita força no trabalho de Célio. Esse desejo-inquietação convida a se reinventar relações variáveis, individualmente moduladas, ainda sem fôrmas, que se projetam para além do ato sexual entre homens ou da ideia de fusão amorosa das identidades — assim, cada retrato vai se fazendo e ganha o nome de quem vestia a peça de roupa desconstruída. Estabelecer um modo de vida homossexual, introduzindo o prazer e o amor onde só se via a lei, a regra ou o hábito, é o que perturba a lógica tradicional da família nuclear e a heteronormatividade. Esse conjunto de retratos bordados pode ser visto como materialização das diversas possibilidades de se tramar relações, construir formas únicas e maleáveis de contatos e conexões com outros homens. Na urdidura do cuidado, do prazer, da intimidade, ética, cumplicidade, companheirismo, erotismo e desejo, as peças evidenciam rearranjos relativamente reversíveis, abertos a outras reconfigurações:

A homossexualidade é uma ocasião histórica de reabrir virtualidades relacionais e afetivas, não tanto pelas qualidades intrínsecas do homossexual, mas pela posição de "enviesado", de alguma forma, as linhas diagonais que ele pode traçar no tecido social, as quais permitem fazer aparecerem essas virtualidades.

Com a fôrma das camisas sociais e com os gestos de ajustá-las e abotoá-las, imagens de um corpo disciplinado rotinizam o estereótipo de masculinidade associado à racionalidade, autoridade, higiene, assepsia, seriedade, profissionalismo, ordem e controle. As camisas brancas de punhos estreitos, em particular, enfatizavam a uniformização de uma identidade coletiva masculina associada ao “neutro”, ao “universal”, valores associados à performance hegemônica de gênero, classe e raça na sociedade burguesa desde pelo menos meados do século XIX.[4] Já contamos com uma história da relação entre moda e cultura queer permeada por expressões de inconformação polivalentes, a apropriação das camisas nas festas, ruas e passarelas afirmam a artificialidade das ordenações binárias do feminino e do masculino, gerando outras configurações, às vezes tão radicais que abalam até mesmo a noção de uma fôrma humana. No entanto, as camisas convencionais empregadas por Célio nesses trabalhos recentes chamam mais atenção para a manutenção dessa fôrma de corpos masculinos, os interstícios ambíguos entre adequação, repressão, docilidade e esconderijo de um lado, e erotismo, despojamento e ironia camp, do outro. Com a desconstrução de cada uma e sua reconstrução “enviesada”, nas direções oblíquas das relações vivas, emerge o desalinho, o entortado, o inadequado.

Em jogo com as casas desabotoadas, alguns buracos e falhas na cobertura da quase-superfície se fazem às vezes mais ou menos evidentes, porém, sempre ruidosos ao olhar mais atento e aproximado. Nitidamente propositais, essas lacunas permitem cada retrato respirar e palpitar na iminência de serem desfeitos novamente ou alterados por mais emendas, outras camadas de pano, alguma pele ou corpo que se interponha ali, antes da parede. A mesma coisa acontece com as sobras ou dobras que se desprendem do retângulo ou do plano como abscessos, apêndices, cicatrizes ou tentáculos. Seriam pistas de um desinteresse ao enquadramento absoluto, evidência da vontade de transbordamento em que cada relação implica. Ambos elementos reforçam o desapego pelo acabamento, o esmero objetivado no bordado também ostenta o erro, o desvio, o remendo e as correções mal-sucedidas, indícios das negociações em termos nunca totalmente sem atritos ou opacidades, entre corpo-mente e objeto-matéria, entre eu e outro — como no que se vive em relação.

A historiadora de arte e psicanalista Rozsika Parker[5] mapeou o processo histórico de declínio do status do bordado do fim da Idade Média até sua consolidação na constelação das “artes menores”. Também no século XIX, com a divisão arte/artesanato, o bordado passava de uma forma de arte elevada praticada por homens e mulheres, particularmente na Inglaterra, para ser visto como ofício inferior e feminino marginalizado ao âmbito doméstico, do que é feito por mulheres e “por amor”. Isso coloca a prática de bordar como central na afirmação de uma ideologia hegemônica da feminilidade. Parker aponta para os dados de pesquisas realizadas no final dos anos 1970 — quando se afirmava que “o bordado é o passatempo preferido de 2% dos homens britânicos, mais ou menos a mesma quantidade daqueles que frequentam a igreja regularmente”. Ela mostra a permanência desse estereótipo e as assimetrias embutidas no interior da divisão sexual do trabalho: “só maricas e mulheres costuram e vão a cultos”.[6]

Mais recentemente, o historiador Joseph McBrinn,[7] e em diálogo direto com Parker, analisa o papel do bordado na criação e subversão da masculinidade: embora se tenha registros da presença do bordado na educação básica de meninos da classe operária no século XIX para acalmá-los; bem como nas dinâmicas tradicionais de ócio dos marinheiros que bordavam presentes para entes queridos sem terem abalada a hipermasculinidade associada a sua profissão; um dos efeitos da centralidade do bordado na “criação da feminilidade” é sua estigmatização como “efeminante” e sua afirmação como uma espécie de “ousado emblema da auto-identificação queer”. Questionando a rigidez da heteronorma em contexto de criminalização da homossexualidade, homens gays bordaram uma codificação íntima de sua vida sexual e afetiva, até mais tarde se ostentar o bordado na celebração camp das possibilidades de sua existência. Longe de afirmar uma essência feminina, gay, queer, dócil e amorosa sobre o bordado, é ainda possível observar como essa prática meticulosa se afirmou historicamente como símbolo de cuidado e amor, sem deixar de se inscrever como uma reivindicação política ruidosa que vai morando nos detalhes.

Ao ver pronto meu retrato, com minha camisa destruída, manchada e recosturada, levando ainda meu nome como título, reconheço algumas dobras de um passado que ainda cabe no corpo, mas que também passa a se desprender de mim. Umas tantas gramas de pó de gesso infiltrado pela pele, entupindo os poros e endurecendo cada articulação, começasse a se esvair. É como se o gesto de Célio pudesse alcançar a musculatura, os nervos, os tendões, liberando o corpo de uma camisa de força interna. No quadro, desfeita e reconfigurada, a camisa chama mais atenção para tudo o que não se conteve e não se moldou. Ao finalizar cada um dos retratos têxteis de perfect friends - perfect lovers com bordado, o trabalho de Célio Braga apresentado em enviesado se insere nessa trama de reinvenções para existência das relações entre homens e da própria ideia de masculinidade, encenando também a repetição do gesto propositivo que vejo enunciado nos últimos versos de um poema de Camila Sosa Villada[8]:

…

Continuemos a nos amar neste pântano de contradições.

Continuemos a nos dar as mãos na rua,

beijos no trem e abraços na grama.

Continuemos a nos vestir de mulheres,

a nos vestir de homem.

Continuemos a perdoar e a amar,

e não nos afastemos do trabalho lento e eficaz do amor…

mesmo que pareça piegas.

A verdade é que há coisas que deixaram de ser óbvias.

[1] Citação direta de As Tentações de Santo Antão de Gustave Flaubert (1874) inscrita na obra Deliriously (2005).

[2] Ernst van Alphen (2006) evoca a noção de skin ego do psicanalista Didier Anzieu para enfatizar a negação da pele como fronteira absoluta entre indivíduo e o mundo no obra de Célio Braga, abordando-a mais como “conectividades íntimas” para afirmar um corpo vulnerável.

[3] De l'amitié comme mode de vie. Entrevista de Michel Foucault a R. de Ceccatty, J. Danet e J. le

Bitoux, publicada no jornal Gai Pied, nº 25, abril de 1981. Tradução por Wanderson Flor do Nascimento e publicada no site Espaço Michel Foucault (2001).

[4] A relação da moda com os estereótipos de gênero é escrutinada por Joanne Entwistle em The Fashionable Body: Fashion, Dress & Modern Social Theory (2015).

[5] Rozsika Parker. The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (1984).

[6] Sobre a presença do bordado na arte brasileira, com indicação de outras autorias masculinas que o empregaram, ver o catálogo da exposição Transbordar: transgressões do bordado na arte, curada por Ana Paula Simioni no Sesc Pinheiros, São Paulo, com textos de Rosana Paulino e Carmen Cordero Reiman (2020-2021).

[7] Joseph McBrinn. Queering the Subversive Stitch: Men and the Culture of Needlework (2020).

[8] Publicado primeiramente em 2015, o poema foi traduzido do espanhol por Joca Reiners e publicado na coletânea A namorada de Sandro(2024).

20/

ENVIESADO

Tálisson Melo

At nineteen, in downtown Madrid, I spent a morning browsing men’s formalwear shops. Black trousers and white shirts dominated the scene, punctuated by a few muted tones of blue, grey, and brown — a landscape without surprises. My mission was to honor my mother’s investment, as she had sent me money to buy “a nicer outfit” for a public event at the university where I was to receive congratulaciones. I looked for a shirt that was both affordable and comfortable, yet capable of “projecting” the seriousness that such recognition seemed to require. Wearing the chosen shirt, I had the sensation that my skin fused with the fabric and that something in me had shifted forever (?!)… Since then, I wore that shirt no more than four times, up until I turned twenty-six. I’ve kept it uselessly hanging in the closet to this day; the fact that it still fits reveals a persistent mold in relation to my more adult body.

Now, at thirty-four, writing this text for Célio Braga’s exhibition — which we’ve titled Enviesado — I accept the idea of entrusting this shirt to his care. A garment marked by a singular memory of the ritualization of a certain masculinity/civility. I know the shirt will be deconstructed into cuts and strips, stretched and wrapped around a wooden frame to become one of the many textile portraits in the series perfect friends - perfect lovers. Each portrait begins with this same act of undoing shirts offered by men with whom Célio maintains some kind of relationship — friends, lovers, partners, colleagues, acquaintances, fathers, sons, brothers, nephews; younger and older, Brazilian and foreign, heterosexual, bisexual, homosexual… Then, they are reconstructed through sewing and embroidery in a new configuration, on rectangular modules measuring 35 x 30 cm. The various colors, patterns, fabric types, and details — darts, pleats, pockets, plackets, labels, buttons, and buttonholes — give shape to the distinctive features of each portrait.

Célio works with things anchored in memories of use — objects that have lived close to the skin, covering and protecting it, but above all serving as molds for what already exists in the world and acts upon the body, and for the way the body positions itself in the world. There is also a gesture of detachment in offering them up, somehow tied to undressing and allowing oneself to be touched — something inherent to the varied relationships between men, which the work reenacts through the obvious presence of touch, of the artist being seen as inhabiting these bodies through the skin, from the inside out. Skin as a mediating matter that merges self and world — “be matter itself!”.[1]

In earlier works, Célio photographed and printed images of skin on paper, which he then pierced and sutured, highlighting its porosity and permeability as an indistinct extension between inside and outside — of and within relationships, affective exchanges.[2] By destroying shirts and reframing their fragments into a new arrangement before sewing them back together — meticulously embroidering the overlapping and entangled parts — Célio’s creative act unfolds through hours of bodily engagement, full of impulses and calculations: a constant negotiation with the materials, with his desire, his technique, and his own body at work.

Upon learning more about Célio’s personal and artistic trajectory and becoming part of the process through which he has been creating these imperfect portraits of friend-lovers, I revisited the questions Michel Foucault answered in a 1981 interview regarding the homosexual way of life:[3]

What kinds of relationships can be established, invented, multiplied, and modulated through homosexuality? How is it possible for men to be together?

To live together, share their time, meals, rooms, leisure, sufferings, knowledge, confidences?

What does it mean to be among men, “undressed,” outside institutional relations—family, profession, obligatory companionship?

The open-ended answer to his own question points to the possibility of reimagining relationships, friendship, intimacy, and communal life. This resonates strongly in Célio’s work. This desire–unease invites the reinvention of variable, individually modulated relationships, still without fixed forms, which project beyond the sexual act between men or the idea of amorous fusion of identities — thus, each portrait gradually takes shape and receives the name of the person who once wore the deconstructed garment. Establishing a homosexual way of life, introducing pleasure and love where only law, rules, or habit were once seen, disrupts the traditional logic of the nuclear family and heteronormativity. This series of embroidered portraits can be seen as the materialization of diverse possibilities for weaving relationships, constructing unique and malleable forms of contact and connection with other men. In the warp of care, pleasure, intimacy, ethics, complicity, companionship, eroticism, and desire, the pieces reveal relatively reversible rearrangements, open to further reconfigurations:

Homosexuality is a historic occasion to open up a whole range of affective and relational virtualities, not only within a couple but on the scale of life, work, friendship, society; to make diagonal lines [oblique, slanted, bent, biased, enviesado…] function in the social fabric.[4]

With the sartorial structure of dress shirts and the gestures of adjusting and buttoning them, images of a disciplined body routinize the stereotype of masculinity associated with rationality, authority, hygiene, asepsis, seriousness, professionalism, order, and control. Narrow-cuffed white shirts, in particular, emphasized the standardization of a collective masculine identity linked to the “neutral” and the “universal,” values associated with the hegemonic performance of gender, class, and race in bourgeois society at least since the mid-19th century.[5] We already have a history of the relationship between fashion and queer culture permeated by multifaceted expressions of nonconformity; the appropriation of shirts in parties, streets, and runways affirms the artificiality of binary orders of femininity and masculinity, generating other configurations, sometimes so radical that they shake even the notion of a human form. However, the conventional shirts employed by Célio in these recent works draw more attention to the maintenance of this mold of male bodies, the ambiguous interstices between conformity, repression, docility, and concealment on one side, and eroticism, casualness, and camp irony on the other. Through the deconstruction of each shirt and its “enviesada” reconstruction — along the oblique lines of lived relationships — misalignment, distortion, and inadequacy emerge.

Playing with unbuttoned buttonholes, some holes and gaps in the coverage of the near-surface sometimes become more or less evident, yet are always noisy to the attentive and close gaze. Clearly intentional, these openings allow each portrait to breathe and pulse on the verge of being undone again or altered by more patches, other layers of fabric, some skin or body that interposes itself there, before the wall. The same happens with the scraps or folds that detach from the rectangle or plane like abscesses, appendages, scars, or tentacles. These might be clues of a disinterest in absolute framing, evidence of the desire to overflow that each relationship implies. Both elements reinforce the detachment from finish; the careful craftsmanship embodied in the embroidery also displays error, deviation, patching, and unsuccessful corrections—signs of negotiations never fully free of friction or opacity, between body-mind and object-matter, between self and other — as experienced in relation.

The art historian and psychoanalyst Rozsika Parker mapped the historical process of the decline in status of embroidery[6] from the late Middle Ages until its consolidation within the constellation of “minor arts.” Also in the nineteenth century, with the division between art and craft, embroidery shifted from an elevated art form practiced by both men and women—particularly in England—to being seen as an inferior craft and a marginalized feminine activity confined to the domestic sphere, done by women “for love.” This situates the practice of embroidery at the center of the affirmation of a hegemonic ideology of femininity. Parker cites research data from the late 1970s—when it was claimed that “embroidery is the favorite pastime of 2% of British men, roughly the same number who attend church regularly.” She highlights the persistence of this stereotype and the asymmetries embedded within the sexual division of labor: “only queers and women sew and go to church.”[7]